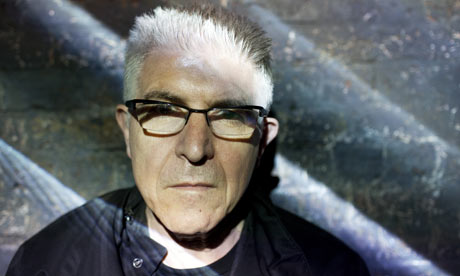

"I started having these experiences," says Fontana, leading me into a coal hole beneath London's Somerset House. "I would be somewhere, and the everyday sounds suddenly seemed as interesting to me as the sounds of any music I could hear inside the concert hall. They just seemed so rich that I wanted to document moments of listening. I came to regard the act of listening as a way of making music. I regarded it as a creative activity – finding music in the environment around me."

This branch of minimalism was outre at a time when post-serial music was the order of the day down at the music conservatory; Fontana even remembers getting into a steaming row with someone who turned out to be Arnold Schoenberg's nephew: "His position was that music had to be complex in order to be beautiful. It was a no-win situation."

But Fontana did win, really. The idea of composing with "found" sounds – of framing or orchestrating what happens around us by chance, of field recordings instead of clarinets – became valid. As John Cage's treasured Indian philosophy says: "Music is continuous; it only stops when we turn away and stop listening."

What Fontana has found for Somerset House, in his River Sounding installation, are the hidden sounds of the Thames. Sixty-two channels of sound (some live, some recorded) through approximately 70 speakers flood the light-wells and coal holes at the foundations of Sir William Chambers's 18th-century grand design. Water trickles melodically through Teddington lock; a ship's bell tolls; a whistling buoy on the estuary duets with a fog horn; the struts of the millennium bridge sing.

"This is one of my favourite spots," says Fontana, as we duck indoors to the Deadhouse. Tombs of the 17th-century Catholic nobility who inhabited earlier buildings on this site punctuate the walls – as does a kind of liquid thunder from a cupboard-size speaker in an alcove.

"What I really love is that it's like the anchor of the building; the bowels of something. The bowels of time, perhaps. I like to make the space seem less material, as if it is moving. As if we are in the bottom of a big ship."

Some of these sounds may be familiar, but many are recordings of places your ears are unlikely to have access to. There are signals from hydrophones (underwater microphones) swimming below Tower Bridge, and accelerometers, attached to the bridge's metalwork, that can hear its private ringing. Whether set up in Vienna, San Francisco, Kyoto or London, Fontana's installations have a clear goal: "My projects are really experiments in perception to break down people's non-listening. I think our culture is in many ways acoustically illiterate, in that people don't grow up learning and recognising or even paying attention to sound patterns in what they would call noise."

Fontana's thoughts run close to those of writer and composer R Murray Shaffer's, who wrote in his 1977 book, The Tuning of the World: "Noise pollution results when man does not listen carefully … Noise is the sounds we have learned to ignore. Noise pollution is being resisted by noise abatement. This is a negative approach. We must seek a way to make environmental acoustics a positive study program." Fontana agrees: "Architects think of sound design as nothing more than controlling the acoustics of a space or dampening them, rather than approaching it in a positive way, the way other elements of design are."

Now that it's so easy to plug in to a sound environment of our own choosing through headphones, such aspirations will perhaps become even more remote, as the idea of a communal soundscape is endangered. One of Fontana's favourite ways of tricking us in to listening is to force our ears and eyes to go their separate ways.

"We learn not to listen by visual cues. If you walk down a street, you're not going to listen to the traffic, but if you heard a recording of the traffic in the woods, you would listen. So the eyes can switch off the ears, and I like to defeat that mechanism." At the lower entrance to Somerset House, for instance, where the Thames used to flow right into the building, your eyes see the dry old river bed below a glass floor, while your ears are drenched with the sound of flowing water.

Fontana's earliest pieces revealed how resonators such as bells are always quietly humming in sympathy to the sounds around them, an idea he returned to last year, in London, with a piece called Silent Echoes, featuring a Buddhist temple bell. It was also the motive behind his 2006 Tate Modern piece, Harmonic Bridge, where he allowed visitors to hear the Millennium bridge. That exchange of sonic energy, plus a love of architecture, keeps Fontana out of pristine gallery spaces and clambering around rooftops or coal holes instead.

"For a long time I didn't use the term sound art, but rather sound sculpture – because of something I read by Marcel Duchamp, in his notes on The Large Glass, 'Musical Sculpture. Sounds lasting and leaving from different places and forming a sounding sculpture that lasts.' So that became almost like a formula for me, the idea of making a sculpture out of sound and defining a space with sound. Sculpture is the physical embodiment of some aspect of the human condition; the condition I try to embody is the act of listening."

Apart from the recent introduction of video footage, little has changed in Fontana's approach over the years. He has, he says, "just got better at it". It is still composition (or, as he more elliptically puts it, "I write music with my ears") but Fontana stops short of any maestro antics.

"I try not to get in the way too much. I feel as if I am bringing something alive, and the less of me, and the more of it, the better. I'm just a means to an end. There's a force out there and I'm just tapping in to it."

River Soundings is at Somerset House, London until 31 May.

No comments:

Post a Comment